When Was the Orthodox Church Left Into Russian Life Again

Left behind? Russian life in Chechnya

After years of violence, displacement and an authoritarian peace, what is life like for indigenous Russians in the near mono-ethnic and mono-organized religion area of Russia?

6 March 2019, nine.24am

Orthodox cemetery on i of the main routes out of Grozny

|(c) Ekaterina Neroznikova. All rights reserved.

Russians are the largest ethnic minority in the Republic of Chechnya, although according to the 2010 census, they make up just 2 percent of the population. Ramzan Kadyrov, the state's leader, calls the republic, "a model of interethnic and interfaith peace and harmony". But what lies behind the rosy picture painted by the official federal and Chechen media?

I recently spent six months in Chechnya, where I was in close contact with both Chechen and Russian communities. The characterization "Russian", all the same, applies here to anyone who self-identifies as such. They might be ethnic Cossacks, Ukrainians or Armenians, just what unites them is their religious identity: they are all part of the Russian Orthodox Church.

Saved by a cross

Co-ordinate to official figures, in 1979 over thirty% of the population of Soviet Chechnya were indigenous Russians. Past 1989 the effigy had fallen, although non by much – they still fabricated up 25% of the population. In 2002, all the same, less than 4 percent of residents were Russian, and past 2010 Chechnya was losing its Russian population faster than any other North Caucasus democracy. It was, finer, a mono-ethnic fellow member of the Russian Federation.

Reports of ethnic cleansing emerged nether Djokhar Dudayev (1991-1996). Oleg Orlov, the head of the Memorial man rights centre's North Caucasus programme told me that both he and Russia's Man Rights Ombudsperson Sergey Kovalev had witnessed harassment of Chechnya'southward Russian-speaking population.

Become our gratis Daily Email

Go one whole story, directly to your inbox every weekday.

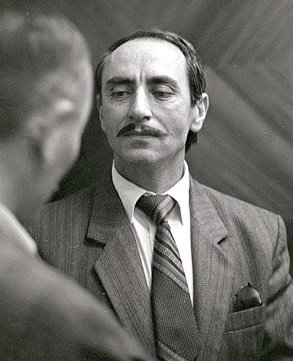

Djokhar Dudayev, outset President of the Chechen Republic of Ichkeria.

| CC BY-SA iv.0 Dmitry Bortko / Wikipedia. Some rights reserved."We encountered lawless and outrageous situations," Orlov told me. "Gangs of bandits were attacking Russian speakers, knowing that the authorities in the de facto contained Chechen Republic of Ichkeria wouldn't touch them. We handed all the information we gathered to [then President] Yeltsin. Only there was no need for it, considering before long afterwards a state of war bankrupt out. "

In the early 1990s, the not-indigenous Chechen function of the population began a mass exodus from the republic, and those who didn't leave were squeezed between Chechen militants fighting for independence on i side, and Russian armed forces on the other.

There were frequent incidents where rebels threatened the lives of both the local Russian and Chechen populations. One ethnic Russian woman, who still lives in the Chechen capital letter Grozny, recalls how she would often hear people saying: "We don't care who you are, y'all're all mixed up with the Chechens here."

Lyusya'south family was in a similar situation. Lyusya (name changed), together with her blood brother and her elderly crippled female parent, live in a small-scale, dilapidated house. Lucy has to do most of the housework and care for her mother herself: her brother spends most of his time alone, absorbed in his reading. I only managed to talk to him once – he showed me some Masonic symbols he'd institute on quondam plans of the city.

Before the state of war with Russia, Lyusya's brother was perfectly normal, merely then something happened that permanently changed him. Russian forces were rounding up men with beards in town — a sign, in soldiers' eyes, of possible allegiance to militant groups — and Lyusya's brother was captured. He besides had a beard. The only reason he wasn't shot, as information technology turned out, was that he was wearing a cross around his neck. He nevertheless had to plead with the men to wait at him and see that he was "one of them" and didn't have to be killed. A cross didn't necessarily save your life at the fourth dimension, but it worked for him.

A story with a happy catastrophe

Information technology'southward hard to say for certain whether Chechen rebels or the local residents harassed Russians. At that place were known cases of fighters bringing lone Russian women flour and h2o to make bread and making certain that none of their boyfriend-rebels offended them in whatsoever way.

Anna Pavlovna (not her real name) retired many years ago. She came to live in Grozny with her hubby when she was young, worked in a factory and was well-respected locally as the 1990s began. Her life wasn't easy – both her hubby and her two sons died young. She now devotes her time to her garden, where she grows fruit, delicious grapes and masses of flowers. And, like most Russians still living in Grozny, she is a staunch churchgoer, and has fifty-fifty planted lots of flowers around the building.

These stories have happy endings. Afterward all, we only hear from the people who take survived. Nosotros don't know what happened to those who didn't.

During the Commencement and Second Chechen Wars, Anna Pavlovna had to exit her business firm several times and movement to the city of Stavropol, over 400km to the northwest; a Chechen neighbour also took her to live in his village with his family for a while. But she remained in Grozny for nigh of the state of war.

Once, during the kickoff campaign, a young Russian soldier was brought to her house. Chechens had institute him in the woods – he had left his mail and was in hiding. Every bit Anna Pavlovna recalls, he was starving and his hair was full of lice.

The men brought the Russian to her home to save his life, though it was unclear who in particular was after him. The rebels might have killed him, but his own side could have convicted him for desertion. The lad lived at Anna Pavlovna'south house for nigh half dozen months, and all that time she and her ex-colleagues (the factory had already airtight down) searched for his family, then he could return home. And they found them in the terminate and his mother came for him – she hadn't even known that her son had been posted to Chechnya.

Some other Anna (again, not her existent proper noun) lives in an old Cossack house, so old that it is already partially complanate into the globe, and inside information technology has a scent of a dying house that she can't get rid of, even so much she washes everything. During the war she was blockaded within these four walls with her blind and ill mother: the neighbouring houses were all occupied by rebel fighters.

The Cossack firm of "Anna", Chechnya.

| (c) Ekaterina Neroznikova. All rights reserved.Like many civilians, she was often visited past rebels in search of nutrient and drink. One day, one of her visitors sat down beside her and placed his hand on her knee. Anna was so scared that she couldn't move, but other "guests" noticed and apace took him out of the house.

The next day, a fighter whom she hadn't seen before turned up at her house and asked whether anyone had been offending her, and after she told him about the previous solar day's incident he said, "They won't be back". And indeed, she didn't see the insolent visitor ever over again.

These stories have happy endings. Afterwards all, nosotros only hear from the people who accept survived. We don't know what happened to those who didn't. In that location are, unfortunately other stories, ones in which Russians were robbed, browbeaten and thrown out of their own houses. They are wary of telling their stories: fear of someone finding out and coming to harass them has taken a firm concord on their consciousness.

Work for "our own people"

Most ethnic Russians who lived in Grozny before the wars worked at plants and factories and found information technology hard to go piece of work in peacetime. Chechens had a similar problem – but at least they had family ties to fall dorsum on.

Finding work in Chechnya is completely dependent on decadent practices: you tin can only get most jobs past offering money in advance, and only with a recommendation from someone who is trusted in the relevant workplace. And information technology's non simply a problem in terms of professional posts in education, medicine or the law: in Chechnya you need to pay to get a job as an ambulance driver.

The clan arrangement is at the heart of everything hither – wellness, education, constabulary and, of course, government. A similar system holds sway in other N Caucasus republics – Dagestan, for example. But because of Chechnya'south atypical indigenous composition, almost posts are filled by Chechens, who in their plow discover jobs for their friends and relations, who are also Chechens. After the war, the only Russians who could notice jobs were those who even so had good relations with Chechens or had married into their families.

"I couldn't observe any work anywhere at outset. I scraped by, taking piece of work on the side, cleaning, even scrounging. But people were always helpful, and Chechens more then than Russians."

Lena moved to Chechnya a few years ago. Earlier that, she lived in Ukraine'southward Donbas: when the disharmonize bankrupt out in that location she immediately tried to settle in Russia and take Russian citizenship. She moved to Saratov, but encountered the same problem as many other refugees – at that place was nothing for her there. And all her attempts to go a Russian passport failed.

"I met a Chechen man on a train, past chance, and he told me to become to Grozny, where information technology would be easier to find piece of work and get Russian citizenship," she says. "He said that there was lots of building going on, and I might even exist offered something. And there was a lot of evolution in the city, so I could find work. At the time I had nothing to lose, and so I went."

Lena arrived in the new, securely corrupt Chechnya: "I couldn't find whatever work anywhere at commencement. I scraped by, taking piece of work on the side, cleaning, fifty-fifty scrounging. But people were always helpful, and Chechens more so than Russians."

She tried to get a job as a cleaner at a hospital, just she would have had to pay viii,000 roubles for the honour, and she didn't take the money. And everyone has to pay, whatever their ethnicity.

Luckily, Lena was pushy, and found herself a room in a hostel for one,000 roubles a month. There was neither a kitchen nor an indoor toilet, simply it was hers. And she should be getting her Russian passport soon.

"I've had to deal with all kinds of attitudes towards me – I'm a single Russian adult female, after all," says Lena, chuckling. In that location were men who wanted her as a lover, just she couldn't bring herself to practise that. "And on the other hand they would say: 'Vesture a hijab, become a Muslim and we'll find you a husband'. But that wasn't for me either: I've e'er been Orthodox, it'south part of our Russian culture," she says with confidence, although in today's Chechnya embracing Islam would simplify her life considerably.

A new world

Over the final two decades, Chechnya has gone through a process of Islamisation. Chechens observed their religion in the past, of course, but it's in the last few years that Islam has become a unifying factor in many ways.

Russians who have converted to Islam oftentimes find it easier to integrate – they can, for case, ally into a Chechen family, which gives them the opportunity to employ family relationships to raise their social condition. Family unit ties are basically the only effective machinery for both climbing a career ladder and but surviving in today's Chechnya.

Within a Russian woman's flat in Grozny

| (c) Ekaterina Neroznikova. All rights reserved.Adopting Islam, and Chechen traditions at the same time, is in no manner compulsory. A certain encouragement to move towards Islam is certainly present, of course, but in general people "Chechenise" nether the influence of their environment.

Nastya met her time to come husband in the early 2000s, when she was working on the effect of noncombatant deaths during the armed conflicts in Chechnya. She was but over 30 and worked in a human rights middle. Her husband, a Chechen, is 15 years older and a lawyer, and they met at a round table discussion near Chechnya.

Nastya's husband had never been married before, and marrying Nastya was clearly a considered and serious decision. They travelled to Moscow's cathedral mosque for their nikah (wedding anniversary). Nastya didn't catechumen to Islam, merely agreed, equally is customary, that any children from their union would be brought up as Muslims. Her husband and so took her dorsum to his village and announced the fait accompli: this is my wife, and she'southward a Russian.

Fitting into the family did non come up easily. Nastya doesn't talk virtually it, but mentions the fact that at one indicate she and her child had to leave her hubby'southward firm for quite some time.

Nastya now lives in the village, and she and her husband have iv children. She has adopted Islam and wears a hijab. And she displays a quality that Chechens value highly in a woman – meekness. The only departure betwixt her and a Chechen woman is that she doesn't speak the language. She tells me that she first needs to learn Arabic and so that she tin can read the Qur'an, and after that she can acquire Chechen. She is a perfect housewife – her business firm is spotless, an exemplary Chechen home. Even seeing me home late at night, she doesn't just walk past the contend, but stops to pull up a weed. Her family say that she is a wonderful wife.

Nastya also believes that everything in her life brought her to 1 thing – her adoption of Islam. She spends a lot of time on her religious didactics, trying to be every bit observant as possible. I didn't know her in the past. It'southward hard to imagine that she once lived an ordinary secular existence.

Entrance to Shelkovskaya. In this poster, the town celebrates 300 years beingness, and thanks Ramzan Kadyrov for a "flourishing state".

| (c) Ekaterina Neroznikova. All rights reserved.Nastya tells me that Islam has not only calmed her soul and helped her find her true path in life, only has made her relations with her own children easier. They, different her, speak Chechen. And given that the basic elements of Chechen national identity are knowledge of the linguistic communication, observance of cultural codes, customary law and religious affiliation, i.e. Islam, she is now not far from being a Chechen woman. Chechen indigenous identity is passed down through the male line, and so despite having a Russian mother, there's no question about her children's identity.

It's rare for a Chechen adult female to ally a Russian man, simply it is possible if the man adopts Islam and speaks Chechen. The state of affairs with a male person Chechen marrying a Russian woman is simpler: Chechen men tin marry both Muslim and Orthodox Russian women. The master issue is the religious and ethnic identity of the children of this matrimony: they have to exist Muslims and exist brought up by their father'southward side of the family. Children of these marriages generally don't encounter themselves every bit Russian.

In the graveyard

Several large villages in Chechnya are regarded by the authorities every bit Cossack settlements. I was able to visit two of them, Shelkovskaya and Naurskaya.

In September 2018, Shelkovskaya held an official celebration of the opening of a new Russian Orthodox church building, and co-ordinate to people attending it, Kadyrov himself flew in with his entourage in two helicopters. The opening marked the 300th ceremony of the founding of the village, and was attended by Orthodox worshippers from all over Chechnya also as from its neighbouring republics. And you can see from the official photos that at that place were a lot of people at that place.

I arrived in the village a month subsequently the opening and found the church closed, with no one around autonomously from a watchmen and a cat. The watchman told me that the edifice was closed immediately later on the so-chosen opening ceremony and there had been no sign of a priest. A search for the local Cossack population brought me to the place where I'd be about likely to find Russian names: the graveyard.

Orthodoxy Cemetery near Staropromyslovskoe Highway, Grozny.

| (c) Ekaterina Neroznikova. All rights reserved.Here, by the grave of a immature serviceman, I found a family unit: his mother, widow and two children. They told me inappreciably whatever homesteads in the village were occupied by Cossacks, and that they were practically lone there. Those Cossacks who weren't killed in the First State of war in the 1990s had fled the surface area, replaced by Chechens from remote settlements. "Information technology's smashing here," they told me. "The land's apartment, so we can farm. There are a lot of Chechens living in the surface area, who've moved to observe a livelihood. In that location was lots of piece of work in the good years, just at present you tin can just about manage to feed yourselves. Then Chechens who've had an educational activity have also left." The women didn't want to talk about why people died in the 1990s – Shelkovskaya was nowhere near whatsoever actual fighting – and quickly began to leave the cemetery.

There is one unusual identify in Shelkovskaya, the Russian Cultural Center, which is to be establish in a tiny room on the ground flooring of the local community centre. The edifice is old and battered – there are thousands of these decommissioned cultural facilities scattered around the old USSR. It stands close to the village'due south primal square, which is totally lacking in interest if you don't count the national flags and photos of Akhmad Kadyrov, the father of Chechnya's present leader, and Vladimir Putin. Sometimes local teenagers get together at the customs centre to play their guitars: during my visit, young men were sabbatum along one wall of the building, singing songs by Timur Mutsurayev, a Chechen vocalizer-songwriter particularly popular for his compositions about state of war and faith, some of which are banned in Russia.

The cultural heart itself contains a table, a few chairs and a glass-fronted cabinet holding commemorative certificates and photographs. Khan-eli Khamayev, leader of the local Cossack folk choir, tells me that the center has been a successful operation for many years and the young musicians go along regular tours around the democracy.

Naurskaya is a village similar to Shelkovskaya, except that its church is older and larger. The building lies backside a loftier fence that backs onto the local police station. I was stopped in front of the church building gates by police officers, who afterwards a brusque chat demanded to run across my ID and searched my car, saying that the appearance of any strangers was considered suspicious "for security reasons".

In front of the St Michael Archangel Orthodox Church, Grozny.

| (c) Ekaterina Neroznikova. All rights reserved.The village has a tiny Cossack guild run by a lively short-haired woman of around 50. Here she created a mini-museum of objects that had come from private houses. "This used to be a adept place: we would lookout films and fifty-fifty hold dances. But there'due south zippo left now – the villages are all in a bad land," she tells me equally we walk along a once handsome central artery of copse. Now it looks very sorry. The trees aren't looked afterwards, the path is a mess: some of the paving stones accept disappeared and the balance lie all higgledy-piggledy. Most of the locals are Chechens – any Russians you come across are probably regular army people posted here for duty. It's generally their children who come to the Cossack society.

"There'south one brave girl. They were told at school that they had to wear hijabs, but she refused, on the grounds that she was a Russian," says the woman. We soon come up across this daughter; she's walking forth the street in a jumper, a short jacket and skinny jeans, which would be dauntless even for Grozny.

When y'all're young

Chechen has never been spoken in Ramzan's house. His mother, who is from neighbouring Ingushetia, only speaks Russian and his father's Chechen isn't very good either. The only person with fluent Chechen is Ramzan himself.

Ramzan is 21, and his early on childhood was spent in Ingushetia, in a refugee camp. He has no concept of Soviet-era Grozny and how people lived there – just he knows what kind of people live in that location today. Conversations among young people, especially the lads, oft end up in discussions almost how good a Chechen y'all are. And here Ramzan has had some problems: both his grandmothers were Ukrainians; both were Orthodox Christians.

He has no problems with his own identity: he is a Chechen – that'south clear and unshakeable. But he can't sympathise why young guys care for Russian girls badly, why they remember of them as easy lays. He has often tried to defend young not-Chechen women from friends wanting to have sex with them - which his mates merely don't get.

One of Ramzan'south grandmothers is cached in Grozny's central Christian cemetery, not far from an onetime canning factory. We went there together to visit her grave. He once went there with a friend, who refused even to go through the gate – as a Muslim, he can't do that.

People in Chechnya today are bombarded with myths around religion: a ban on going into an Orthodox cemetery or church is just i of them. Religious rites, such as processions with a cross at Easter, seem like medieval absurdities to young people, and people of their parents' generation take also lost the habit.

That said, about adults are fine when it comes to Russians' organized religion and traditions. When they were young, Chechnya wasn't a mono-indigenous republic.

Can we stop Large Tech getting within our heads?

Social media and e-commerce giants are influencing what we buy, how nosotros vote and who we honey. Now the state of war in Ukraine threatens to splinter the global internet further and militarise surveillance like never before.

What does this hateful for the nigh bones of man rights: the liberty to recall?

Shoshana Zuboff Author of 'The Age of Surveillance Capitalism: The Fight for a Homo Hereafter at the New Frontier of Power' and professor emerita at Harvard Business concern Schoolhouse

Susie Alegre International human rights lawyer and author of 'Liberty to Think: The Long Struggle to Liberate Our Minds'

Chair: Mary Fitzgerald Director of expression at the Open Society Foundation, leading on global work to support journalism and tackle disinformation

Source: https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/left-behind-russian-life-chechnya/

0 Response to "When Was the Orthodox Church Left Into Russian Life Again"

Post a Comment