According to the Reading How Are Scholarly Journals and Popular Magazines Different

We've all read the headlines at the supermarket checkout line: "Aliens Abduct New Jersey School Teacher" or "Quadruplets Born to 99-Year-Old Woman: Exclusive Photos Inside." Journals like the National Enquirer sell copies by publishing sensational headlines, and almost readers believe simply a fraction of what is printed. A person more interested in news than gossip could buy a publication similar Time, Newsweek or Observe. These magazines publish information on electric current news and events, including recent scientific advances. These are not original reports of scientific enquiry, however. In fact, most of these stories include phrases like, "A group of scientists recently published their findings on..." So where practice scientists publish their findings?

Scientists publish their original research in scientific journals, which are fundamentally unlike from news magazines. The articles in scientific journals are non written by journalists – they are written past scientists. Scientific articles are not sensational stories intended to entertain the reader with an amazing discovery, nor are they news stories intended to summarize recent scientific events, nor even records of every successful and unsuccessful research venture. Instead, scientists write articles to describe their findings to the customs in a transparent manner.

Scientific journals vs. pop media

Within a scientific article, scientists present their enquiry questions, the methods by which the question was approached, and the results they accomplished using those methods. In addition, they present their analysis of the data and depict some of the interpretations and implications of their piece of work. Considering these articles report new piece of work for the first fourth dimension, they are called primary literature. In contrast, articles or news stories that review or report on scientific research already published elsewhere are referred to every bit secondary.

The manufactures in scientific journals are unlike from news manufactures in another mode – they must undergo a procedure chosen peer review, in which other scientists (the professional peers of the authors) evaluate the quality and merit of inquiry before recommending whether or not it should be published (run into our Peer Review module). This is a much lengthier and more rigorous process than the editing and fact-checking that goes on at news organizations. The reason for this thorough evaluation by peers is that a scientific article is more a snapshot of what is going on at a certain time in a scientist'south research. Instead, it is a part of what is collectively called the scientific literature, a global archive of scientific noesis. When published, each article expands the library of scientific literature bachelor to all scientists and contributes to the overall knowledge base of the discipline of scientific discipline.

Comprehension Checkpoint

Articles published in scientific literature are considered primary literature when

Scientific journals: Degrees of specialization

At that place are thousands of scientific journals that publish inquiry manufactures. These journals are various and tin can be distinguished according to their field of specialization. Among the most broadly targeted and competitive are journals like Prison cell, the New England Periodical of Medicine (NEJM), Nature, and Science that all publish a broad diverseness of research articles (meet Figure ane for an example). Cell focuses on all areas of biology, NEJM on medicine, and both Science and Nature publish manufactures in all areas of science. Scientists submit manuscripts for publication in these journals when they feel their piece of work deserves the broadest possible audience.

Just below these journals in terms of their reach are the top-tier disciplinary journals like Belittling Chemistry, Applied Geochemistry, Neuron, Journal of Geophysical Research, and many others. These journals tend to publish broad-based research focused on specific disciplines, such as chemistry, geology, neurology, nuclear physics, etc.

Next in line are highly specialized journals, such as the American Journal of Potato Research, Grass and Fodder Science, the Journal of Shellfish Enquiry, Neuropeptides, Paleolimnology, and many more. While the research published in various journals does not differ in terms of the quality or the rigor of the science described, it does differ in its degree of specialization: These journals tend to exist more specialized, and thus appeal to a more limited audience.

All of these journals play a critical role in the advancement of science and dissemination of data (run into our Utilizing the Scientific Literature module for more information). Withal, to empathise how science is disseminated through these journals, you must first understand how the manufactures themselves are formatted and what information they comprise. While some details about format vary between journals and even between articles in the same journal, there are broad characteristics that all scientific journal articles share.

Comprehension Checkpoint

Journals that are narrow in focus, such as the American Journal of Potato Research, do non advance scientific discipline.

The standard format of journal articles

In June of 2005, the periodical Science published a research study on a sighting of the ivory-billed woodpecker, a bird long considered extinct in Due north America (Fitzpatrick et al., 2005). The piece of work was of such significance and broad interest that it was displayed prominently on the embrace (Figure two) and highlighted past an editorial at the front of the journal (Kennedy, 2005). The authors were aware that their findings were likely to be controversial, and they worked especially hard to make their writing articulate. Although the article has no headings within the text, information technology tin easily exist divided into sections:

Championship and authors: The title of a scientific article should concisely and accurately summarize the inquiry. Hither, the title used is "Ivory-billed Woodpecker (Campephilus principalis) Persists in North America." While it is meant to capture attending, journals avoid using misleading or overly sensational titles (you tin can imagine that a tabloid might utilise the headline "Long-dead Giant Bird Attacks Canoeists!"). The names of all scientific contributors are listed every bit authors immediately after the title. You may be used to seeing one or maybe two authors for a volume or newspaper article, just this commodity has seventeen authors! It's unlikely that all seventeen of those authors sat downwards in a room and wrote the manuscript together. Instead, the authorship reflects the distribution of the workload and responsibility for the inquiry, in addition to the writing. By convention, the scientist who performed most of the work described in the article is listed first, and it is likely that the get-go author did most of the writing. Other authors had unlike contributions; for case, Gene Sparling is the person who originally spotted the bird in Arkansas and was subsequently contacted by the scientists at the Cornell Laboratory of Ornithology. In some cases, but not in the woodpecker commodity, the concluding author listed is the senior researcher on the projection, or the scientist from whose lab the project originated. Increasingly, journals are requesting that authors particular their verbal contributions to the research and writing associated with a detail report.

Abstract: The abstract is the first function of the commodity that appears right afterwards the list of authors in an commodity. In it, the authors briefly draw the research question, the general methods, and the major findings and implications of the work. Providing a summary like this at the beginning of an article serves 2 purposes: First, it gives readers a way to determine whether the commodity in question discusses enquiry that interests them, and second, it is entered into literature databases as a means of providing more information to people doing scientific literature searches. For both purposes, it is important to have a short version of the total story. In this case, all of the critical information nigh the timing of the study, the type of data collected, and the potential interpretations of the findings is captured in four straightforward sentences as seen beneath:

The ivory-billed woodpecker (Campephilus principalis), long suspected to be extinct, has been rediscovered in the Big Wood region of eastern Arkansas. Visual encounters during 2004 and 2005, and analysis of a video prune from April 2004, confirm the existence of at least 1 male person. Acoustic signatures consistent with Campephilus brandish drums as well have been heard from the region. Extensive efforts to detect birds away from the primary encounter site remain unsuccessful, simply potential habitat for a thinly distributed source population is vast (over 220,000 hectares).

Introduction: The key research question and important background data are presented in the introduction. Considering scientific discipline is a process that builds on previous findings, relevant and established scientific knowledge is cited in this section and then listed in the References section at the finish of the article. In many articles, a heading is used to ready this and subsequent sections apart, just in the woodpecker article the introduction consists of the first iii paragraphs, in which the history of the refuse of the woodpecker and previous studies are cited. The introduction is intended to lead the reader to understand the authors' hypothesis and means of testing it. In addition, the introduction provides an opportunity for the authors to bear witness that they are aware of the work that scientists have done before them and how their results fit in, explicitly edifice on existing knowledge.

Materials and methods: In this section, the authors describe the research methods they used (come across The Practice of Science module for more information on these methods). All procedures, equipment, measurement parameters, etc. are described in detail sufficient for some other researcher to evaluate and/or reproduce the enquiry. In addition, authors explain the sources of error and procedures employed to reduce and measure the uncertainty in their information (run into our Uncertainty, Error, and Confidence module). The detail given here allows other scientists to evaluate the quality of the data nerveless. This section varies dramatically depending on the blazon of enquiry washed. In an experimental study, the experimental set-upwards and procedure would be described in item, including the variables, controls, and handling. The woodpecker study used a descriptive research approach, and the materials and methods section is quite short, including the means by which the bird was initially spotted (on a kayaking trip) and later photographed and videotaped.

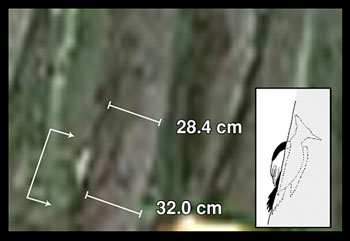

Results: The data collected during the research are presented in this department, both in written form and using tables, graphs, and figures (come across our Using Graphs and Visual Data module). In improver, all statistical and data analysis techniques used are presented (see our Statistics in Science module). Importantly, the data should be presented separately from any estimation by the authors. This separation of data from estimation serves two purposes: First, it gives other scientists the opportunity to evaluate the quality of the bodily data, and second, information technology allows others to develop their own interpretations of the findings based on their background noesis and feel. In the woodpecker article, the data consist largely of photographs and videos (see Figure 3 for an example). The authors include both the raw information (the photograph) and their analysis (the measurement of the tree trunk and inferred length of the bird perched on the trunk). The sketch of the bird on the right-mitt side of the photo is also a form of assay, in which the authors have simplified the photograph to highlight the features of interest. Keeping the raw data (in the form of a photo) facilitated reanalysis by other scientists: In early 2006, a squad of researchers led by the American ornithologist David Sibley reanalyzed the photograph in Effigy 3 and came to the conclusion that the bird was not an ivory-billed woodpecker after all (Sibley et al, 2006).

Discussion and conclusions: In this section, authors nowadays their interpretation of the data, often including a model or idea they feel best explains their results. They also nowadays the strengths and significance of their piece of work. Naturally, this is the most subjective section of a scientific enquiry article as information technology presents interpretation as opposed to strictly methods and data, but it is not speculation past the authors. Instead, this is where the authors combine their experience, background knowledge, and inventiveness to explain the data and utilise the data as evidence in their estimation (see our Data Analysis and Estimation module). Often, the word department includes several possible explanations or interpretations of the data; the authors may then describe why they back up i detail interpretation over the others. This is not just a process of hedging their bets – this how scientists say to their peers that they take done their homework and that at that place is more than one possible caption. In the woodpecker article, for instance, the authors go to bully lengths to describe why they believe the bird they saw is an ivory-billed woodpecker rather than a variant of the more common pileated woodpecker, knowing that this is a likely potential rebuttal to their initial findings. A final component of the conclusions involves placing the current piece of work dorsum into a larger context by discussing the implications of the work. The authors of the woodpecker article do so by discussing the nature of the woodpecker habitat and how information technology might be better preserved.

In many manufactures, the results and discussion sections are combined, but regardless, the data are initially presented without interpretation.

References: Scientific progress requires edifice on existing knowledge, and previous findings are recognized by directly citing them in whatsoever new work. The citations are collected in one list, commonly called "References," although the precise format for each journal varies considerably. The reference listing may seem similar something you don't actually read, but in fact it can provide a wealth of information about whether the authors are citing the most recent work in their field or whether they are biased in their citations towards certain institutions or authors. In addition, the reference section provides readers of the commodity with more information about the particular enquiry topic discussed. The reference list for the woodpecker article includes a wide multifariousness of sources that includes books, other periodical articles, and personal accounts of bird sightings.

Supporting material: Increasingly, journals make supporting material that does non fit into the article itself – like extensive data tables, detailed descriptions of methods, figures, and animations – available online. In this example, the video footage shot past the authors is available online, forth with several other resources.

Comprehension Checkpoint

Scientists who wish to replicate the research described in a journal article may pay item attending to the __________ section.

Reading the main literature

The format of a scientific article may seem overly structured compared to many other things you read, only it serves a purpose by providing an archive of scientific research in the primary literature that we tin can build on. Though isolated examples of that archive go equally far dorsum every bit 600 BCE (see the Babylonian tablets in our Description in Scientific Enquiry module), the showtime consistently published scientific periodical was the Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Lodge of London, edited by Henry Oldenburg for the Majestic Order beginning in 1666 (see our Scientific Institutions and Societies module). These early scientific writings include all of the components listed in a higher place, but the writing style is surprisingly different than a modern journal article. For example, Isaac Newton opened his 1672 commodity "New Theory Well-nigh Light and Colours" with the post-obit:

I shall without farther anniversary acquaint you, that in the commencement of the Year 1666...I procured me a Triangular glass-Prisme, to try therewith the celebrated Phenomena of Colours. And in order thereto having darkened my chamber, and made a small hole in my window-shuts, to permit in a convenient quantity of the Suns low-cal, I placed my Prisme at his entrance, that it might be thereby refracted to the opposite wall. Information technology was at first a very pleasing divertissement, to view the vivid and intense colours produced thereby; but after a while applying my self to consider them more circumspectly, I became surprised to run into them in an ellipsoidal course; which, according to the received laws of Refraction, I expected should have been circular. (Newton, 1672)

Newton describes his materials and methods in the first few sentences ("... a pocket-sized hole in my window-shuts"), describes his results ("an oblong form"), refers to the work that has come before him ("the received laws of Refraction"), and highlights how his results differ from his expectations. Today, nevertheless, Newton's statement that the "colours" produced were a "very pleasing divertissement" would be out of place in a scientific article (Figure iv). Much more typically, modern scientific articles are written in an objective tone, typically without statements of personal stance to avoid any advent of bias in the interpretation of their results. Unfortunately, this tone ofttimes results in overuse of the passive vocalization, with statements like "a Triangular glass-Prisme was procured" instead of the wording Newton chose: "I procured me a Triangular glass-Prisme." The removal of the first person entirely from the articles reinforces the misconception that science is impersonal, deadening, and void of creativity, lacking the enjoyment and surprise described by Newton. The tone can sometimes be misleading if the report involves many authors, making it unclear who did what work. The best scientific writers are able to both present their work in an objective tone and make their own contributions clear.

The scholarly vocabulary in scientific manufactures can exist another obstacle to reading the primary literature. Materials and Methods sections often are highly technical in nature and tin be confusing if you lot are non intimately familiar with the blazon of enquiry beingness conducted. There is a reason for all of this vocabulary, however: An explicit, technical description of materials and methods provides a means for other scientists to evaluate the quality of the data presented and can often provide insight to scientists on how to replicate or extend the research described.

The tone and specialized vocabulary of the mod scientific article can go far hard to read, only agreement the purpose and requirements for each section can help you lot decipher the main literature. Learning to read scientific articles is a skill, and like whatever other skill, it requires practice and feel to master. Information technology is not, yet, an impossible task.

Strange as information technology seems, the nigh efficient style to tackle a new commodity may exist through a piecemeal arroyo, reading some just not all the sections and not necessarily in their social club of appearance. For instance, the abstract of an article will summarize its cardinal points, simply this section can often be dense and hard to understand. Sometimes the cease of the article may be a better place to get-go reading. In many cases, authors present a model that fits their data in this last section of the article. The word section may emphasize some themes or ideas that tie the story together, giving the reader some foundation for reading the article from the first. Even experienced scientists read articles this way – skimming the figures get-go, perhaps, or reading the discussion and then going back to the results. Often, information technology takes a scientist multiple readings to truly sympathise the authors' work and incorporate it into their personal knowledge base in society to build on that knowledge.

Comprehension Checkpoint

In 1672, Isaac Newton published his research on light and colors. He included a statement about how entertaining prisms were. Newton'due south piece of work

Building knowledge and facilitating discussion

The process of science does not terminate with the publication of the results of enquiry in a scientific article. In fact, in some means, publication is just the beginning. Scientific journals also provide a means for other scientists to respond to the work they publish; like many newspapers and magazines, most scientific journals publish letters from their readers.

Unlike the common "Letters to the Editor" of a newspaper, however, the letters in scientific journals are usually disquisitional responses to the authors of a research study in which alternative interpretations are outlined. When such a letter is received by a journal editor, it is typically given to the original authors so that they can respond, and both the letter and response are published together. Nine months after the original publication of the woodpecker article, Science published a letter (chosen a "Annotate") from David Sibley and iii of his colleagues, who reinterpreted the Fitzpatrick team'due south information and concluded that the bird in question was a more common pileated woodpecker, not an ivory-billed woodpecker (Sibley et al., 2006). The team from the Cornell lab wrote a response supporting their initial conclusions, and Sibley'due south team followed that up with a response of their own in 2007 (Fitzpatrick et al., 2006; Sibley at al., 2007). Every bit expected, the research has generated significant scientific controversy and, in add-on, has captured the attending of the public, spreading the story of the controversy into the pop media.

For more information about this story run into The Case of the Ivory-Billed Woodpecker module.

Summary

Using a brief history of scientific writing, this module provides an introduction to the structure and content of scientific journal articles. Key differences between scientific journals and popular media are explained, and basic parts of a scientific article are described through a specific instance. The module offers communication on how to arroyo the reading of a scientific commodity.

Key Concepts

-

Scientists brand their research available to the community by publishing it in scientific journals.

-

In scientific papers, scientists explain the inquiry that they are building on, their research methods, data and information analysis techniques, and their estimation of the data.

-

Understanding how to read scientific papers is a disquisitional skill for scientists and students of science.

Source: https://www.visionlearning.com/en/library/Process-of-Science/49/Understanding-Scientific-Journals-and-Articles/158

0 Response to "According to the Reading How Are Scholarly Journals and Popular Magazines Different"

Post a Comment